All About the Effective Rate

TOPICS

Taxes

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Morgan Walker

Veronica Nigh

Senior Economist

When it comes to federal taxes, you know I'm all about that effective rate,

'Bout that effective rate, not brackets

I'm all 'bout that effective rate, 'bout that effective rate, not brackets.

We’re shamelessly adapting Megan Trainor’s lyrics, but when it comes to farmers and federal taxes we’re all about the effective rate, not the baseline rate found in the tax rate brackets. When House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady makes public the committee’s tax bill tomorrow, it will once again be how all of the provisions interact to produce the effective tax rate that farmers pay to which we pay attention.

There are three main factors that have an impact how farmers are impacted by the federal tax code. The first is that most farms file through the individual code, not the corporate code. The second is that the vast majority of the average farm’s assets are tied up in illiquid long-term assets. The third is that farm income is predictability unpredictable.

How Farms File

During the Agriculture and Tax Reform: Opportunities for Rural America hearing before the House Committee on Agriculture on April 5, 2017, Dr. James Williamson of the USDA Economic Research Service explained that “the vast majority of farms are organized as pass-through entities that are not subject to income tax themselves. Rather, the owners of the entities are taxed individually on their share of income.” That statement is backed up by data from the 2012 Census of Agriculture, which details that 93 percent of U.S. farms, representing 72 percent of total sales, filed through the individual code, either as sole proprietors or partnerships.

Capital Intense

Beyond knowing that farms tend to have an impressive amount of assets, but those assets are illiquid, USDA ARMS data from 2015 revealed that the average farm business balance sheet carried $1,109,012 in farm assets. Of those assets, however, only 8 percent are considered current assets, those assets like cash and other assets that are expected to be converted to cash within a year. For farm businesses those non-cash assets include: livestock and crop inventory, purchased inputs, cash invested in growing crops, prepaid insurance and cash. That leaves 92 percent of farm business assets tied up in non-current assets, better known as long-term investments where the full value will not be realized within the accounting year. For farm businesses, examples include investments in cooperatives, land and buildings, farm equipment, breeding animals and the operators’ dwelling.

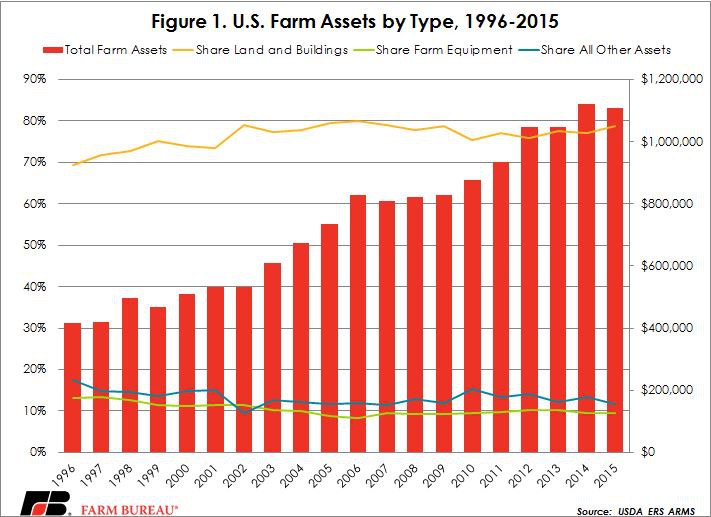

Far and away, however, buildings and land are farmers and ranchers most valuable assets. In fact, in 2015, real estate accounted for 79 percent of all farm business assets (current and non-current combined). But this isn’t anything new, as proven by ERS’s ARMS data which goes back to 1996. In figure 1, we see that land and buildings as a share of total assets have predominantly stayed in the 70 to 80 percent range, while equipment averaged 10 percent of total assets over the same period. If data were available even further back, the same trend would be expected: after all, agriculture has always been land rich and cash poor.

This dynamic of the farm business balance sheet just described is a key reason why farmers care greatly about how tax provisions that deal with how capital investments are treated, such as capital gains, like-kind exchanges and depreciation. The federal income tax system has historically taxed gains on the sale of assets held for investment or business purposes and for more than one year at rates lower than on other sources of income. Lower capital gains rates encourage investment over immediate consumption.

Tax provisions like Section 301 like-kind exchanges recognize that trading one track of land for another or an old tractor for a new one are events where farmers and ranchers are re-investing and improving their businesses, activities that should be celebrated, not saddled with immediate capital gain taxes. Without like-kind exchanges, capital gains would increase further the cost of these re-investment activities.

Even when an old piece of equipment is traded in for a new one, purchasing new machinery and equipment is an expensive endeavor. The ability to accelerate the depreciation of those assets lowers the total cost of owning the equipment by reducing taxable income.

Farm Income is Volatile

Changes to the tax code that would increase the taxes farmers pay on these purchases, would increase the cost of purchases and make maintaining and improving farm businesses more costly. Certainly, no business wants to experience increased costs, but the consequences of those fluctuations are even more pronounced in farming and ranching.

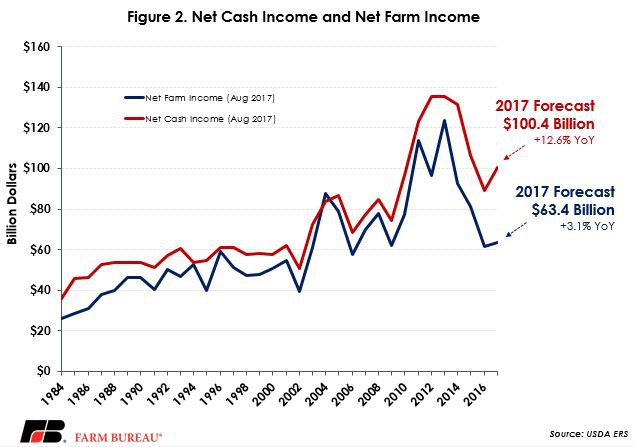

According to a 2017 ERS study titled “Farm Household Income Volatility: An Analysis Using Panel Data from a National Survey,” the median change in total income between years of larger scale commercial farms--those responsible for about 80 percent of the value of U.S. agricultural output--was about eight times larger than for nonfarm households. Indeed, according to USDA ERS, net farm income fell by half between 2013 and 2016.

While ERS projects that net farm income will be up 3 percent in 2017 compared to the decade low experienced just last year, it is still more than $20 billion below the 10-year average of $85 billion. (A recent Market Intel reviewed farm income trends, Net Farm Income Does a Dead Cat Bounce.) There aren’t many wage earners, also filing through the individual tax code that experience this level of variation in their incomes. Tax tools like those described above, and other like cash accounting not discussed here, allow the industry to self-insure and limit its exposure to wild swings in prices and thus farm income. We eagerly await tomorrow’s tax plan, the individual pieces and how they interact, with a keen eye on the overall effective rate, not just individual pieces.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL