AEWR Methodology Change a Blow to Growers

photo credit: Colorado Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Veronica Nigh

Senior Economist

Here is the recipe that the U.S. Department of Labor used to create the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) Methodology for the Temporary Employment of H-2A Nonimmigrants in Non-Range Occupations in the United States final rule. Step one: Copy the proposed rule of the same name released on Dec. 1, 2021. Step two: Paste. Step three: Sprinkle in some references to having received comments from a range of stakeholders from the public, private and nonprofit sectors, but fail to incorporate any of the suggestions. Step four: Add a dash of “it’s not our job” in response to some of the comments received. Step five: Publish the final rule, which “is adopting the methodology proposed in the 2021 AEWR NPRM without change,” in the Federal Register on Feb. 28, 2023. Barring any last-minute change of heart or legal action, this new wage regime goes into effect today, Thursday, March 30.

An Overview of the Final AEWR Rule

On the surface, understanding the new AEWR calculation is relatively easy. The wage for the majority of positions, defined by six Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) codes, will continue to be determined by the Farm Labor Survey (FLS) conducted by USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. All other positions will be paid according to the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) survey conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. But as with most things, the devil is in the details; unfortunately for the farmers who will have to try to implement the new AEWR final rule, there are devils around every corner.

First, the “easy” part – that which stays the same. The FLS is conducted four times per year and results in semiannual reports. The second report of the year, typically released in November, includes an annualized weighted-average combined hourly wage rate for field and livestock workers. This wage rate is what the current AEWR for all H-2A employees is based upon and what the majority of positions will continue to be based upon. The six job categories (with their corresponding SOC codes) that will continue to use this AEWR include: graders and sorters (45-2041); agricultural equipment operators (45-2091); farmworkers: crop, nursery, and greenhouse (45-2092); farmworkers: farm, ranch, and aquacultural animals (45-2093); agricultural workers, all others (45-2099); and packers and packagers (53-7064).

Now to the harder part. Any position that is determined to fall outside of the six classifications listed above will now be subject to an individual AEWR based on the OEWS. If there is a state-specific wage rate for that SOC in the OEWS, the AEWR will be based on that wage. If there is no state-level OEWS for that SOC, the AEWR will be based on the national wage rate for the SOC in the OEWS. This, of course, means that for some positions, the wage rate will no longer be state/regional specific.

How big of a deal is this bifurcated methodology? In the final rule, DOL contends that 98% of H-2A positions will continue to be paid under the previous methodology, i.e., the single-rate AEWR within the field and livestock workers (combined) category determined by the FLS. However, they are basing this assumption on a review of previous years of H-2A position determinations – before the new, and more complex, rules applied. This is an important distinction because the final rule stipulates that “for agricultural labor or services to be performed by H-2A workers that cannot be encompassed within a single SOC code, the Department proposed to determine the AEWR using the SOC code assigned to the employer’s job opportunity with the highest applicable AEWR.” This likely means that under the new rules, a much larger share of positions will no longer be classified as falling within the field and livestock workers (combined) category. DOL fails to recognize this reality with their assessment that only 2% of positions will be subject to SOC-specific AEWRs.

A personal favorite example from the final rule of how this might play out on the farm:

“An H-2A job opportunity that requires a worker to perform hand-harvest work and to pick-up farmworkers, according to a regular schedule, from employer-provided housing or a centralized pick-up point, in a van used only for passenger transport, on public roads ( e.g., from a motel to the farm), and drive them to the place(s) of employment to perform hand-harvest work, may be assigned SOC code 53-3053 (Shuttle Drivers and Chauffeurs), in addition to SOC code 45-2092 (Farmworkers and Laborers, Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse). SOC codes 53-3053 and 45-2092 are subject to different AEWR determinations.” SOC code 45-2092 is subject to the AEWR determination within the field and livestock workers (combined) category; 53-3053 is subject to the SOC-specific AEWR determination. “When determining the employer's H-2A wage obligation, and the higher of the two AEWRs (i.e., the AEWR applicable to SOC code 53-3053 and the AEWR applicable to SOC code 45-2092) is the single AEWR for evaluating the employer's wage obligations for all of the work performed for this job opportunity.”

To put this change in a real-world perspective, in the state of New York in 2021 the state wage rate for chauffeurs (53-3053) was $19.52 an hour. The AEWR for field and livestock workers (combined) category in New York in 2021 was $14.99 an hour. Even though the worker will spend most of their time performing hand-harvest work, the new rule would require the New York farm employer to pay an additional 30% for that employee (assuming a 40-hour work week).

Perhaps you’re not an employer, so this small example doesn’t resonate. We modelled a limited version of what these two changes (bifurcated AEWR methodology and revised SOC determinations) could mean on two farms. The small farm employs 10 H-2A employees, the large farm employees 70 H-2A employees. Under the previous rule all of the employees on each farm were paid equally, the AEWR for field and livestock workers (combined) category. Under the new rule, however, it is likely that this would change. We assumed that on the small farm (10 employees) that eight employees would continue to be classified as farmworkers - crop, nursery and greenhouse (45-2092) and be paid the combined rate, but that one worker would now be classified as a first-line supervisors of farm workers (45-1011) and one worker would now be classified as a light truck driver (53-3033). On the large farm we made similar changes but adjusted for size. On the large farm 60 employees would continue to be classified as farmworkers - crop, nursery and greenhouse (45-2092) and be paid the combined rate, but three workers would now be classified as first-line supervisors of farm workers (45-1011) and three workers would now be classified as light truck drivers (53-3033). How big of a deal could this possibly be?

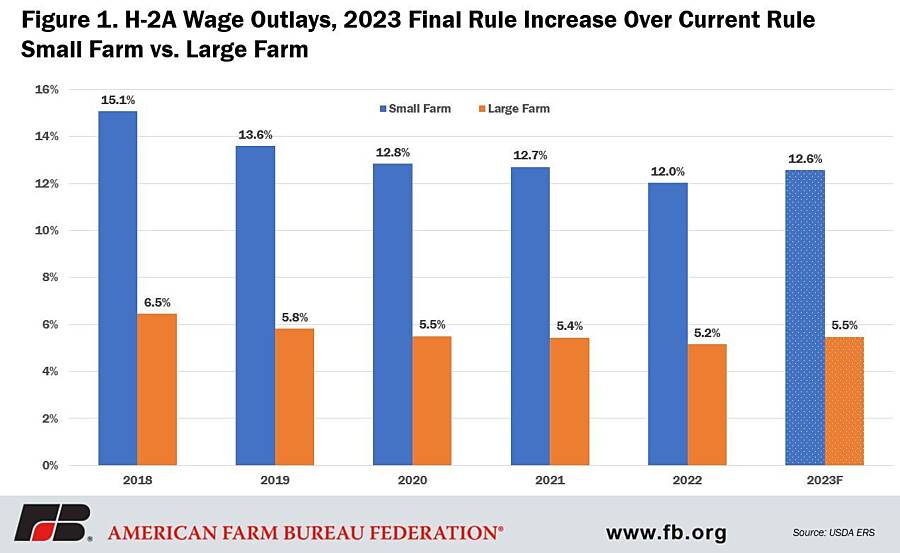

In Figure 1 we see that applying the above changes to the sample farms would have a significant impact on the wage outlays of each farm, but particularly the small farm. Across a national average, on the small farm the new methodology would have increased wage outlays by 15.1%, 13.6%, 12.8%, 12.7% and 12% in 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively, and an estimated 12.6% in 2023. Across a national average, on the large farm the new methodology would have increased wage outlays by 6.5%, 5.8%, 5.5%, 5.4% and 5.2% in 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively, and an estimated 5.5% in 2023. The increases in 2023 are estimated because the OEWS program doesn’t release the May 2022 estimates until April 25, 2023.

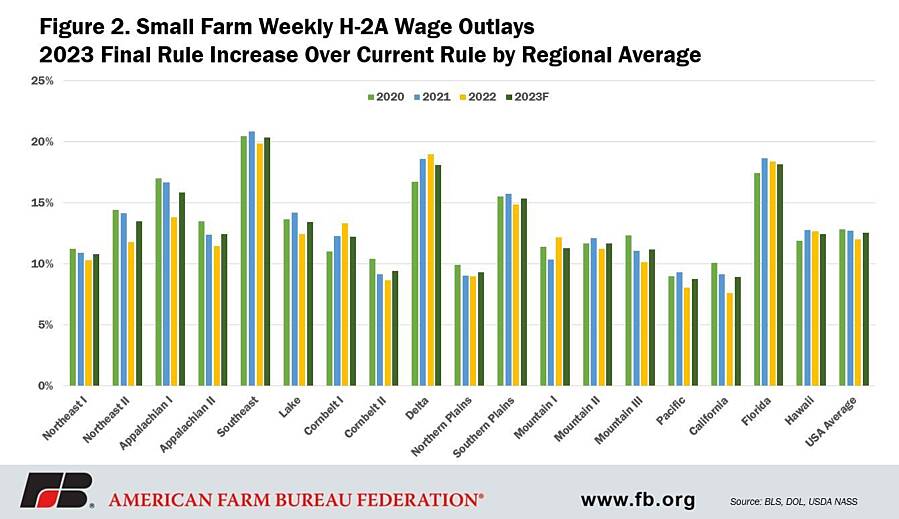

As growers are quick to point out, however, no one pays the national average rate, so it’s important to explore the regional/state specifics. In Figures 2 and 3 we see that every region would experience higher wage outlays under the new rule, but that the range across regions is significant. The smallest increase in 2022 would have occurred in California, where the small and large growers would have paid 7.6% and 3.3% more in wages, respectively. The largest increase in 2022 would have occurred in the Southeast region. The small growers in the Southeast region would have paid an average of 19.8% more in wages, while the large grower would have paid 8.5% more under the new rule. (Definitions of the Farm labor regions can be found on page 26 of the November 2022 Farm Labor report.)

Beyond Wages

Beyond wages, the additional complications for growers are not insignificant. We will focus on two complications here. The first is that employers would now face two wage changes each year. One Federal Register notice would announce annual adjustments to the AEWRs based on the FLS, effective on or about Jan. 1, and a second Federal Register notice would announce annual adjustments to the AEWRs based on the OEWS survey, effective on or about July 1. In the final rule, DOL, demonstrating a sizable break from reality, notes that it “considers the likelihood of confusion or disruption among workers subject to different temporary agricultural employment certifications to be low.”

The other complication to consider here is the lack of predictability in the SOC determination for positions. Per the final rule (definitions in brackets are the author’s own),

“The Department reiterates that the evaluation of tasks associated with an employer's job opportunity and SOC code assignment is not new in the H-2A program and declines to introduce a new, separate administrative process. Due to the time-sensitive nature of receiving and processing H-2A applications under the statute, the SWA [state workforce agencies] will continue to evaluate an employer's job opportunity in the first instance—and determine the appropriate SOC code(s) for the job opportunity—when it reviews an employer's job order for compliance with 20 CFR part 653, subpart F, and 20 CFR part 655, subpart B. The SWA will continue to enter the SOC code assigned to the employer's job opportunity on the Form ETA-790, Agricultural Clearance Order. After the employer files its H-2A Application for Temporary Employment Certification, the OFLC CO [Office of Foreign Labor Certification Certifying Officer] will continue to perform a secondary evaluation of the employer's application and job order, including SOC coding. As is currently the case, the CO may determine whether a different SOC coding is necessary, for example, based on additional information received during processing.”

While it is true that state workforce agencies have been assigning SOC codes to positions, those determinations have not had a significant impact on employers. As was demonstrated above, under the final rule, the impact of those determinations could be considerable. As DOL points out, they could also change, after the Office of Foreign Labor Certification reviews the state workforce agency’s evaluation. For employers this introduces a whole new level of uncertainty as they try to estimate the ultimate wage outlays for the year.

Legislative Attempts to Intervene

Some astute legislators have picked up on the significance of the “modest” changes that DOL is introducing with the AEWR final rule. Two attempts are currently underway to try to push pause on the final rule. The first is an effort by congressional leaders to introduce a resolution of disapproval under the Congressional Review Act (CRA) for the recent DOL rule on the new AEWR methodology. If the CRA joint resolution of disapproval is enacted, the AEWR final rule would go out of effect immediately and “shall be treated as though such rule had never taken effect.” Learn more about CRA here. The second effort, the bipartisan Farm Operations Support Act, introduced by Sens. Jon Ossoff (D-Ga.) and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), temporarily resets the AEWR at 2022 levels. While the national average AEWR in 2022 was $15.56, a sizable 6.4% increase over the 2021 level, it is certainly preferrable to the 2023 national average AEWR of $16.62 and the new AEWR final rule described above that goes into effect on March 30, 2023.

Summary

The new AEWR final rule will inflict considerable wage increases on farmers of all sizes who use the H-2A program. While DOL may be under the impression that the final rule it has crafted focuses on “prevent[ing] future adverse effect” with surgical precision, the reality is that it is more like the child’s game of Operation. The patient (both grower employers and H-2A employees) is awake, will feel every misstep and may not survive the operation, no matter what the surgeon’s intentions.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL