2022 Farm Profitability Outlook: Production Expenses Up, Net Farm Income Down

TOPICS

USDA

photo credit: Arkansas Farm Bureau, used with permission.

Daniel Munch

Economist

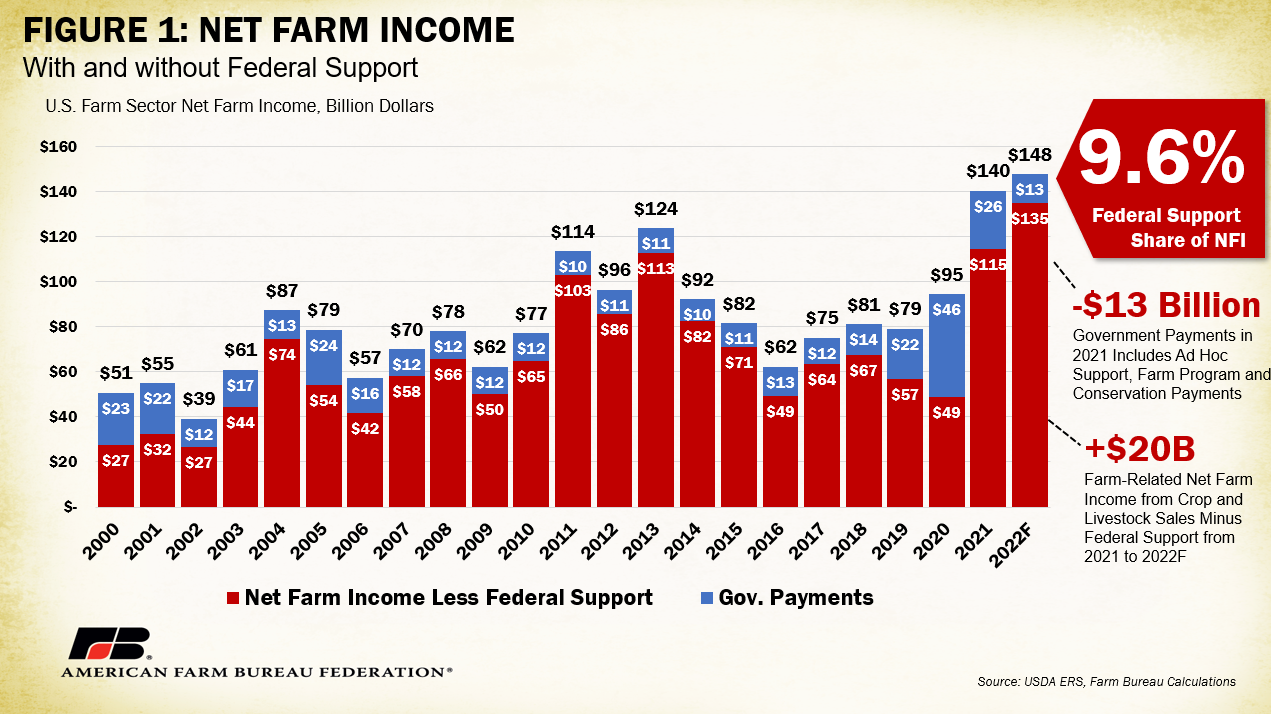

USDA’s most recent Farm Sector Income Forecast, released Feb. 4, anticipates a slight decline in net farm income for 2022. U.S. net farm income, a broad measure of farm profitability, is currently forecasted at $113.7 billion, down 4.5%, or $5.4 billion, from 2021’s $119.1 billion. If realized, this would represent the first drop in net farm income after two consecutive years of gains. However, the expected net farm income for 2022 would be 82% higher than the decade low of $62 billion in 2016 and 15.2% above the 2001-2020 average of $98.7 billion when adjusted for inflation.

Net Farm Income Breakdown

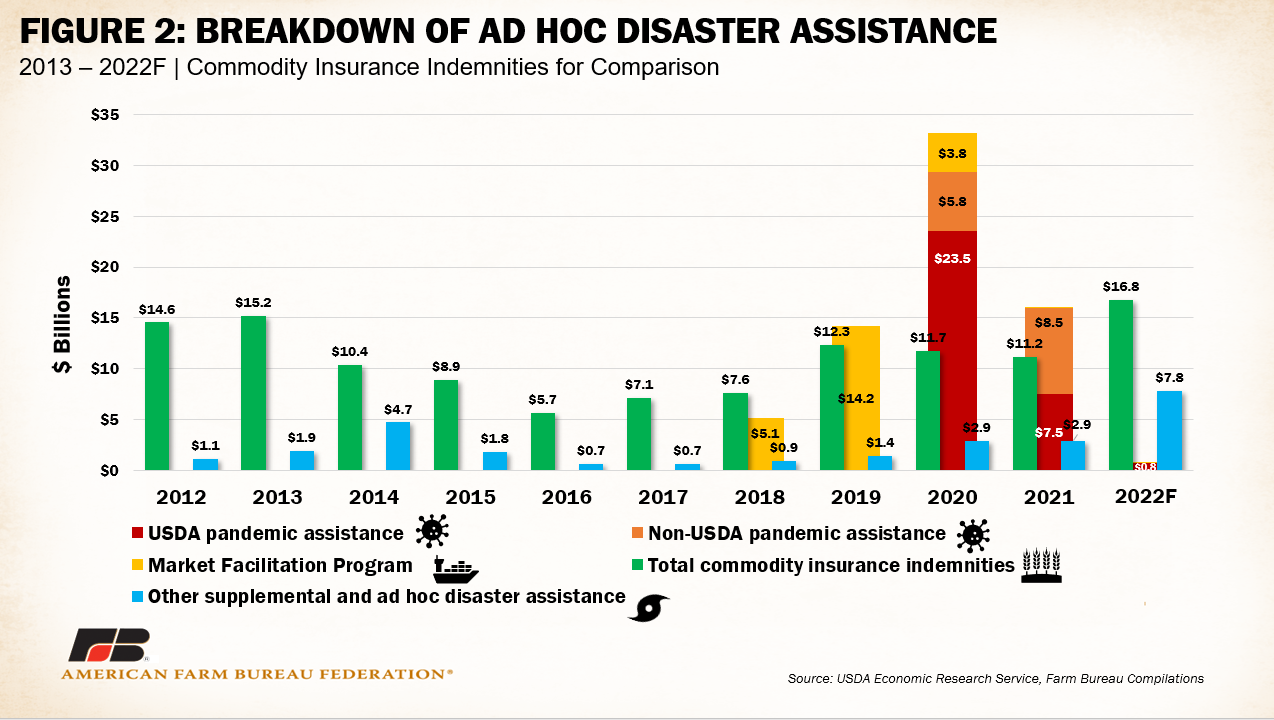

A significant portion of the decline in net farm income is linked to an expected dramatic decrease in federal support to producers assuming much less pandemic-related disaster assistance. Direct government payments are forecast to decrease by $15.5 billion, a whopping 57%, between 2021 and 2022. As displayed in Figure 2, the decrease corresponds to reductions in both USDA pandemic assistance, which includes payments from the Coronavirus Food Assistance Programs and other pandemic assistance to producers, and non-USDA pandemic assistance programs, such as funds from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program.

From 2021 to 2022, federal payments though USDA’s pandemic assistance initiatives are expected to drop $4.4 billion, from $7.8 billion to $3.4 billion, or 56%, and non-USDA pandemic assistance is expected to disappear completely, at a difference of $8.73 billion from 2021. In addition to the reduced pandemic-related payments, the Market Facilitation Program, which provided a series of direct payments to farmers and ranchers impacted by trade retaliation, ended in 2021 and will not be part of net farm income going forward. The “other supplemental and ad hoc disaster assistance” category includes payments from the Wildfire and Hurricane Indemnity Program (WHIP+), Quality Loss Adjustment Program, and other farm bill designated-disaster programs. These programs are expected to remain steady moving forward since they are separate from the COVID-19 pandemic. In Figure 2, total commodity insurance indemnities, which are triggered in the event of revenue or yield loss for growers who have purchased crop insurance, are not direct government payments but are included for comparison. Commodity insurance indemnities are expected to increase in 2022 by 49%, or $5.5 billion, moving from $11.3 billion to $16.8 billion. This increase is perhaps a result of increased crop insurance enrollment by those who received a WHIP+ payment who must purchase crop insurance or Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program coverage (when crop insurance is not available) for the next two available crop years under program requirements.

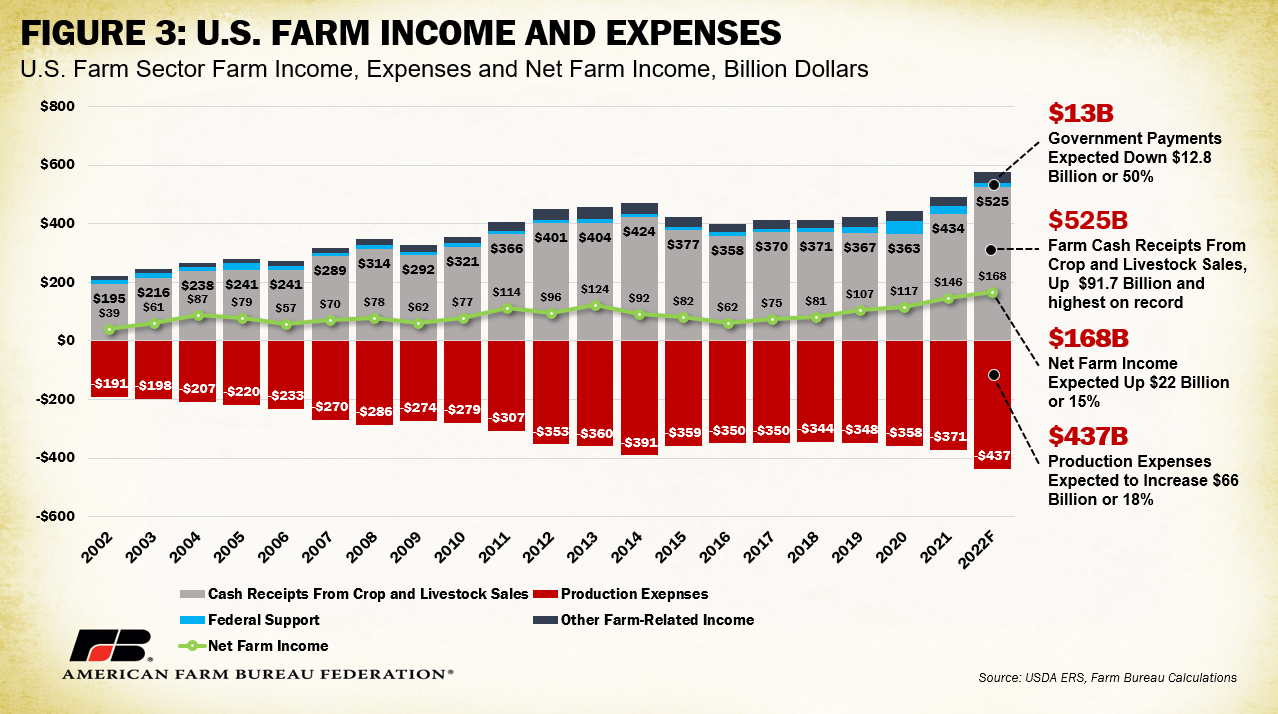

An analysis of additional pieces of the net farm income statement reveals that cash receipts for sales of agricultural commodities like crops and livestock are expected to increase by $29.3 billion, an increase of 6.8% from 2021, reaching $461.9 billion in 2022. This includes a $12 billion, or 5.1%, increase in additional cash returns for crops and an additional $17.4 billion, or 8.9%, for livestock products. On the cost side, production expenses, including operator dwelling expenses, are forecasted to increase by $20.1 billion, or 5.1%, reaching $411.6 billion in 2022, the highest production costs farmers have ever faced. This includes increases in costs like cumulative feed, which is expected to increase nearly $4 billion, or 6.1%, to $68.9 billion. Fertilizer, lime and soil conditioner costs are expected to increase $3.4 billion, or 12%, from $28.5 billion to $31.9 billion. Typically, fertilizers represent about 15% of a crop farmer’s costs and an increase of this magnitude could be crushing for some producers without the substantial increases in revenue. Other increased production costs in the manufactured inputs category include pesticides, which are expected up $308 million, or 2%, from $16.9 billion to $17.2 billion and fuels and oils are also expected up 2%, or $329 million, from $15.9 billion to $16.2 billion. Farmers and ranchers are facing the same challenges other Americans are facing with the increased cost of electricity, which is expected to increase $433 million, or 5.4%, for producers, from $6.1 billion to nearly $6.6 billion. Other farm-related income, which includes things like income from custom work, machine hire, commodity insurance indemnities and rent received by operator landlords, is estimated to increase by $6.2 billion, or 18%, from $32.7 billion to $38.9 billion in 2022. When all these factors are accounted for, the resulting decrease in forecasted net farm income becomes more apparent, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Other Farm Financial Indicators

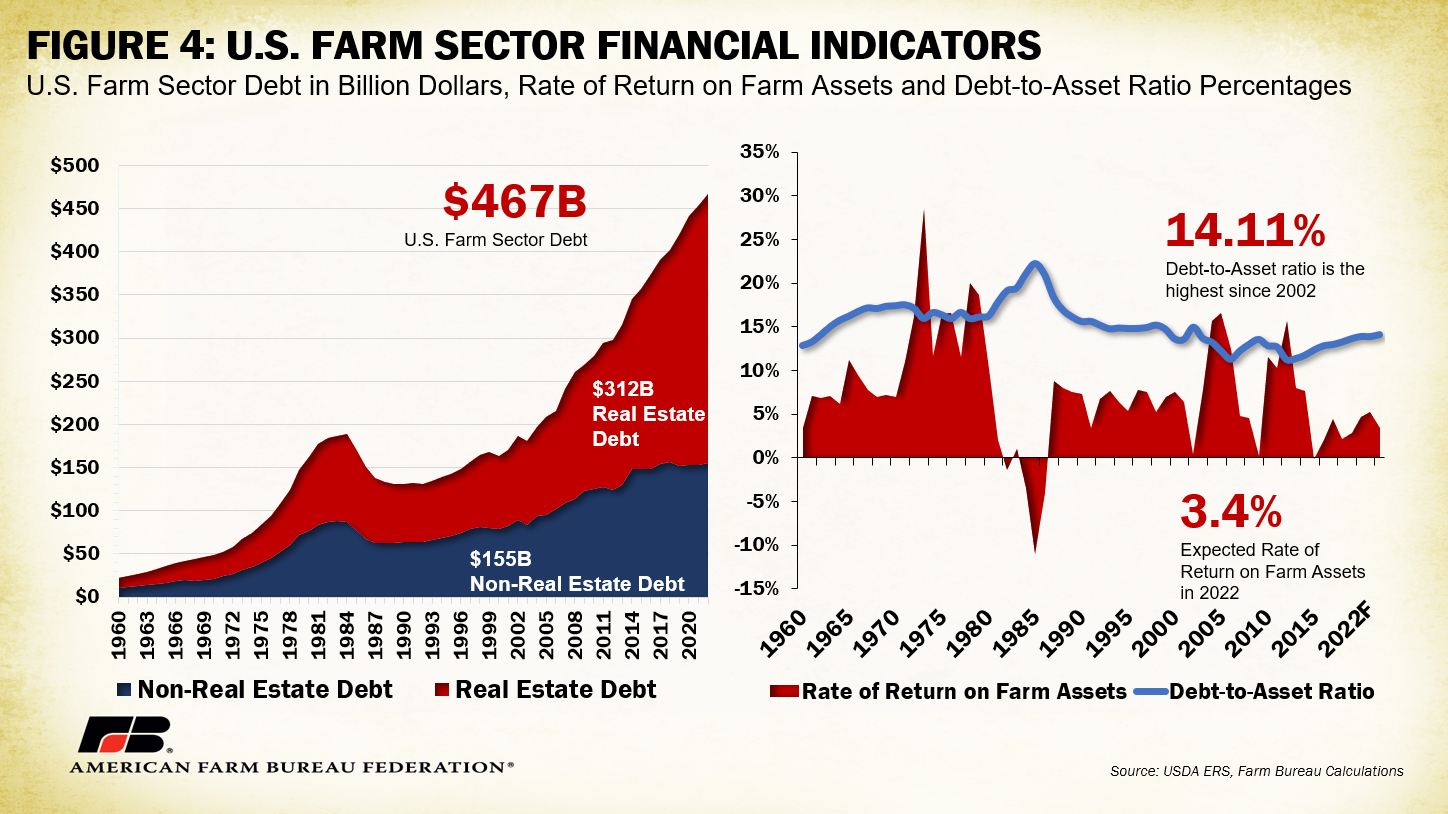

USDA’s Farm Sector Income Forecast also provides expectations of farm financial indicators that can give insight into the overall financial health of the farm economy. During 2022, U.S. farm sector debt is projected to increase $13.05 billion, or nearly 3%, to a record $467.4 billion. Nearly 67% of farm debt is in the form of real estate debt, as for the land to grow crops and raise livestock. Real estate debt is projected to increase $10.2 billion to a record-high $311.9 billion, largely due to an increase in land values across the country. Non-real estate debt, or debt for purchases of things like equipment, machinery, feed and livestock, is projected to increase only slightly to $155.4 billion. The value of the farm assets that are purchased via farm debt, including farmland, animals, machinery and vehicles and crops in inventory, is projected to reach $3.31 trillion, $42.2 billion higher than 2021. Most of this increase, $26.8 billion, is also attributed to higher farmland values. The important piece here is that the value of assets being purchased with debt is rising and it will continue to be important for farmers and ranchers to pay down debt and cover interest in order to maintain a healthy balance sheet.

Based on 2022 debt and asset levels, USDA expects the debt-to-asset ratio to be over 14% for 2022, which would be the highest since 2002, meaning farmers have increased their borrowing. Every year since 2012, aside from 2021, during which they marginally decreased, debt-to-asset levels have climbed higher.

Working capital, which takes into consideration current assets and liabilities, is the amount of cash and cash-convertible assets minus amounts due to creditors within 12 months. In 2022, working capital is projected to fall by $3.1 billion, or 3.3%, to $93 billion, which is the first decline since 2016, and remains 30% below levels in 2014, when farmers and ranchers held $121 billion in working capital. Lower levels of working capital would suggest that many U.S. farmers have just enough capital to service their short-term debt, as long as interest rates remain stagnant.

Another metric that highlights the concern about farmer profitability in 2022 is the rate of return on assets. For 2022, the rate of return on assets is projected at less than 3.5%. The rate of return in agriculture has been less than 6% for eight consecutive years and is in stark contrast to the 10%-to-16% returns experienced from 2010 to 2012. This essentially means that farmers and ranchers are seeing smaller revenues or returns for the investments made in the cost of production and in assets used to produce a farm product. Figure 4 highlights U.S. farm sector debt, the debt-to-asset ratio and the rate of return on farm assets.

Summary

USDA released the most recent estimates for 2022 net farm income, providing a very early estimate of the farm financial picture. For 2022, USDA anticipates a slight decline in net farm income, moving from $119.1 billion in 2021 to $113.7 billion, a decrease of 4.5%. While a majority of the 2022 net farm income is expected to be produced by crop and livestock cash receipts, an increase in production costs and a decrease in ad hoc government support results in an overall reduction of forecasted net farm income. Farmers and ranchers are most concerned about the increase in production costs, particularly in fertilizer and other inputs, the cost of which will challenge their ability to reach above breakeven. This is apparent in USDA’s estimate for farm financial indicators, which shows a decline in working capital and an increase in farm debt. Much of the concern across farm country now turns to having enough working capital to cover short-term debt while interest rates remain low, but rapid increases to interest rates could put farmers leveraged with a larger amount of debt in a more difficult financial position. Managing financial risk by lowering production costs and diversifying revenues, or even supplementing revenues with off-farm income, are some of the solutions farmers are considering. The anticipation of a weaker year-end balance sheet, despite above average net farm income, is a strong reminder of the challenges farmers and ranchers face.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL