The Payoff of Investing in Research for Growing Economies

TOPICS

SustainabilityGuest Author

Special Contributor to FB.org

photo credit: Arkansas Farm Bureau, used with permission.

Guest Author

Special Contributor to FB.org

By Dr. Gbola Adesogan and Jim Harper

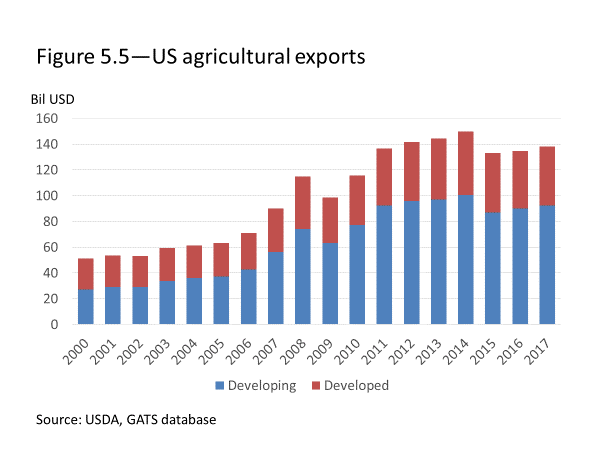

U.S. agricultural exports have been growing for decades, thanks to strong demand from developing economies. Part of this growth has been fueled by U.S. assistance and academic research. In addition to benefits abroad, these foreign investments bring major returns to the U.S.

Since 2000, countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America have driven growth of nearly $100 billion in annual U.S. agricultural exports. Not long ago, many of these countries received more financial assistance than they spent on U.S. goods. Today, they represent some of our largest trading partners. For example, South Korea went from being a net recipient of U.S. aid to importing more than 2 million metric tons of soybeans, and U.S. exports to the country increased from $2.55 billion to $5.69 billion in 2016.

Feed the Future began in 2010; it was reaffirmed with overwhelming bipartisan support as part of the 2016 Global Food Security Act.

It is important to note that U.S. foreign aid represents less than 1 percent of the U.S. government’s budget. For the agricultural sector, the U.S. provided 57 countries with $1.2 billion in assistance in 2017 through the U.S. Agency for International Development. By comparison, that year’s U.S. agricultural exports were worth $138 billion.

Feed the Future, the U.S. government’s global hunger and food security initiative, involves several government agencies that work together to support country-driven approaches to address root causes of hunger and poverty and forge solutions to food insecurity. It helps countries transform their agricultural sectors to sustainably feed their people and depend less on foreign aid.

Feed the Future began in 2010 and was reaffirmed with overwhelming bipartisan support as part of the Global Food Security Act of 2016.

Clearly, U.S. investments abroad also help needy people in those countries. Within the past decade, the Feed the Future program has helped an estimated 23.4 million more people escape extreme poverty, 3.4 million children live free of stunting or malnutrition and 5.2 million families avoid hunger.

Research to solve hunger and malnutrition

Moral imperatives also drive the U.S. to generosity. Unfortunately, global hunger is rising again after years of decline. This trend is very troubling because it means more suffering and instability in the world, which encourages emigration. By addressing hunger and food insecurity, we are not only doing the right thing, we are also reducing immigration and increasing national security.

One way to reach and teach the world to grow food is through research for development. The U.S. invests about $100 million annually through universities in agricultural research assistance.

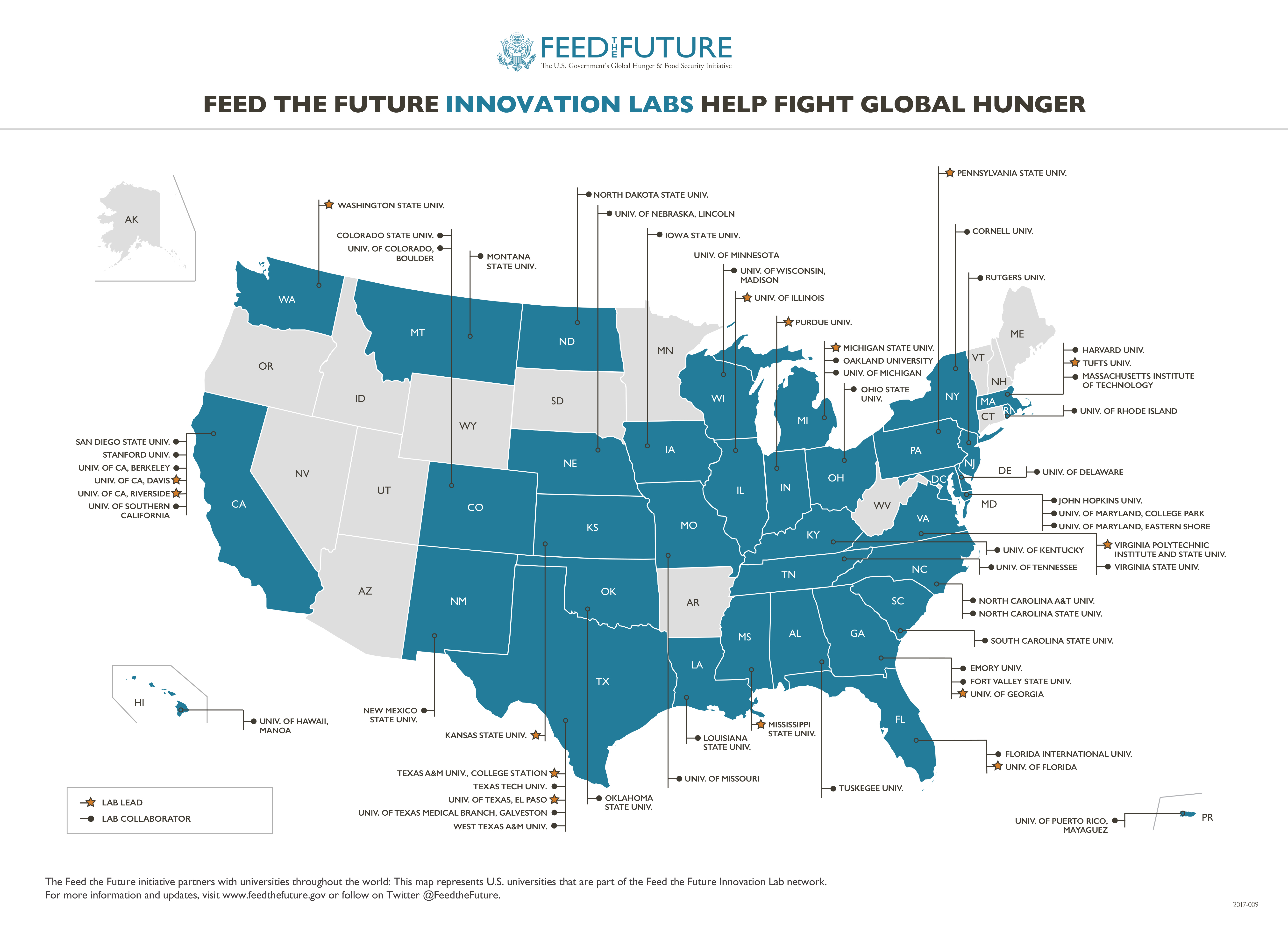

As an example, our research team at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences received USAID funding in 2015 to establish the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Livestock Systems, one of more than 20 similar centers at universities across the U.S. These Innovation Labs are authorized by Title XII of the Foreign Assistance Act, which passed with strong bipartisan support. Innovation Labs are partnerships between USAID, about 70 U.S. universities and foreign institutions. They leverage the expertise of U.S. universities, particularly those in the land-grant system, by conducting research that solves the most pressing agriculture and food problems in developing countries in partnership with their own researchers.

Innovation Labs also work with various U.S. government-funded programs such as the Farmer to Farmer program, which sends U.S. farmers and consultants abroad to train smallholder farmers to improve the productivity of their farms.

Political leaders have been very supportive of the work of the Innovation Labs. In referring to our Innovation Lab, which is also funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Rep. Ted Yoho (R-Fla.) paraphrased an old proverb about how “we need to teach these countries to fish, rather than to keep giving them fish.” That is exactly what we do. Overall, senators on both sides of the aisle have voiced strong support for foreign assistance and described it as a critical strategy for enhancing national security and building goodwill towards the U.S.

Technology for prosperity

Many of the Innovation Lab research projects abroad result in solutions to problems faced by farmers in the U.S. Examples include a new satellite-based insurance index in Kenya developed by the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Assets and Market Access at the University of California, Davis, which helps poor women protect their cattle from drought, or the Integrated Decision Support System developed by the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Small-Scale Irrigation at Texas A&M university, which is used for flood forecasting. Our Innovation Lab participates in a global effort to eradicate a plague affecting goats, deer and sheep, called Peste des Petits Ruminants, and the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Integrated Pest Management at Virginia Tech is working on controlling various invasive crop pests in foreign countries. These efforts will help to control dangerous pests and infectious diseases abroad and prevent them from getting to the U.S.

Other Innovation Labs, like the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Genomics to Improve Poultry at UC Davis and the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Sorghum and Millet at Kansas State University are learning about traits such as those for disease resistance and heat tolerance that can improve crop and livestock genetics, health and production in the U.S. Also, some like our Innovation Lab, the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Nutrition at Tufts University and the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Soybean Value Chain Research at University of Illinois, are improving the nutrition of infants, children and pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Some technologies developed abroad with foreign aid have already returned the favor to the U.S. For instance, the benefits of USAID-funded research on developing resistant sorghum lines to greenbug aphid in the 1980s have been valued at $750 million annually. Current research in Africa on the sugarcane aphid, which is a pest in the entire sorghum-producing region of the U.S., could be even more valuable because in 2013 alone, U.S. growers lost $8 million due to this sorghum pest, when up to 50 percent of grain sorghum yield in infested fields was lost. Discoveries in Africa could be beneficial to fighting the disease on American soil.

The payoff of investing in research in growing economies fuels our domestic economy now and lays a solid foundation for the future.

Dr. Gbola Adesogan is the director of the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Livestock Systems, and a professor of ruminant nutrition at the University of Florida. Jim Harper manages communications for the Innovation Lab.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL